Kuva

Kuva is a small town in the Fergana region of the Republic of Uzbekistan, located 20 km from the regional center, the city of Fergana. Like many cities in the Fergana Valley, it has a very respectable age. The exact date of the founding of the city has not yet been established. However, archaeological research is underway on the territory of the city, and perhaps soon we will learn many secrets associated with the formation of human civilization in this area. In the meantime, scientists, with the precision of surgeons, excavating time layers date the age of the settlement to the 3rd century BC.

Kuva is a small town in the Fergana region of the Republic of Uzbekistan, located 20 km from the regional center, the city of Fergana. Like many cities in the Fergana Valley, it has a very respectable age. The exact date of the founding of the city has not yet been established. However, archaeological research is underway on the territory of the city, and perhaps soon we will learn many secrets associated with the formation of human civilization in this area. In the meantime, scientists, with the precision of surgeons, excavating time layers date the age of the settlement to the 3rd century BC.

One of the oldest cities in the Ferghana Valley is the city of Kuva.No one knows what this settlement was called at the very beginning, but the Arab conquerors who came here in the X century called this place "Kubo", which means the same as "tepa" in Turkic, namely "hill" or hill. And this is not surprising, because the new city was built on the ruins of the former, gradually settling mud-brick settlement, which in turn was built on the ruins of the previous one. From the same Arab sources, it becomes clear that Kuva was a typical Eastern city consisting of three parts: the citadel of Shahristan, surrounded by a city wall and rabads, commercial and artisan settlements around the city. According to the same data, during the early Middle Ages, the city may have been larger and more beautiful than the ancient capital of the Ferghana Valley - Aksikent, possessed economic and political power, trade and crafts flourished in it.

Research on the ancient settlement began in the first third of the last century, during the construction of the Big and South Fergana Canals, and then continued in 1951, but only the expedition of 1956-1957 brought great scientific discoveries.

And the first result of archaeological excavations was confirmation of the version about the unprecedented flowering of crafts in ancient Kuva. Today there is already scientific evidence that the city was a center for the production of glass for the entire Fergana Valley. Glass was so cheap in Couva that numerous household items were made from it, including chamber pots for babies. This is also confirmed by the Chinese chronicles of the 8th-9th centuries, which claim that the then ruler of Fergana gave the “secret of glass making” by sending his glassblowers to the “heavenly realm”, who, having mastered it, found there quartz sand suitable for making glass.

To the north of the previously discovered “shakhristan”, scientists managed to unearth an entire block of well-preserved buildings, streets and squares. The most interesting find was a cult complex - a Buddhist temple. Statues of various deities of the Buddhist pantheon, destroyed images of the Buddha himself, and fragments of monumental sculpture were discovered in the temple. This allowed scientists to assume that before the Arab invasion in the Fergana Valley, along with Zoroastrianism, there were pockets of established Buddhism.

With the acquisition of independence in Uzbekistan, interest in the Kuva excavations has increased again. Scientists have long been haunted by the question of the supposed homeland of Abu-l-Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathir al-Fergani, the famous medieval astronomer and mathematician who served the caliphs of Merv, Cairo and Baghdad, who gained fame in Europe under the name Alfraganus.

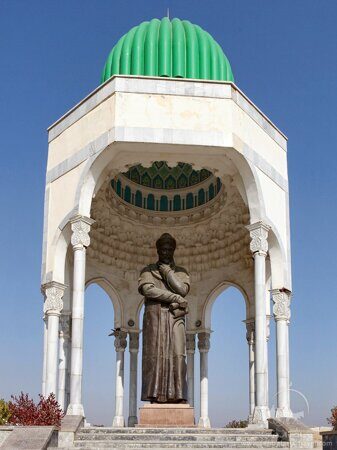

It was the Ferghana scientist-archaeologist, candidate of historical sciences Gennady Ivanov who suggested that the birthplace of the famous scientist could be medieval Kuva. Based on strict scientific data and the results of the latest archaeological expedition to the ancient settlement, the fact of the famous scientist’s presence in Kuva was confirmed, which led to the opening in 1998 of a memorial complex in the homeland of the great Ferghana citizen.

The memorial complex is located between the highway leading to the regional center and the territory of ancient Shakhristan, with a fragment of archaeological excavations. The fortress wall has been restored and against its background a wonderfully beautiful garden has been laid out, 350 meters long with fountains along its entire axis. On the heights of Shakhristan there is a pavilion with the Al-Farghoni monument, from which two oval staircases lead to the lower garden.

And today Kuva, not only a beautiful city surrounded by green gardens and vineyards with the sweetest pomegranates, today the Kuva excavation and significant memorial have become a bright decoration of the tourist route in the Fergana Valley.

Kuva ancient settlement

The Kuva settlement, located on the territory of the regional center of the Fergana region of the same name, first attracted attention at the beginning of the 20th century. Its size, as well as a large amount of ancient ceramics and other archaeological objects on the surface of the monument, made it possible even then to compare the hill, called by the locals Kei kubod tepa, with the city of Kubo by Arabic-speaking authors of the 10th century.

The Kuva settlement, located on the territory of the regional center of the Fergana region of the same name, first attracted attention at the beginning of the 20th century. Its size, as well as a large amount of ancient ceramics and other archaeological objects on the surface of the monument, made it possible even then to compare the hill, called by the locals Kei kubod tepa, with the city of Kubo by Arabic-speaking authors of the 10th century.

Written sources cover the history of Kuva extremely sparingly. According to Arab geographers, Kubo (as the city was called in Arabic at that time) in the 10th century. was one of the largest cities in the valley. Some authors (Al-Mokaddasi) considered it even larger and more beautiful than the capital of Fergana - Akhsiket (BGA, III. p. 48).

From a source covering the events of the beginning of the USSR. it is known that the governor of the Fergana ruler was in Kubo. The important political and economic position of Kuva is also indicated by the presence of a mint in the city. The fact that coins were minted in Couva in the 10th century was proven back in the late 50s. In addition, during excavations in Kuva, most of the coins published to date were found, practically unknown outside the Fergana Valley. O.I. Smirnova, who identified the Kuvan coins, believes that they were cast in the 7th-VT2nd centuries. in Kuva itself (Smirnova O.I., 1977. P. 53). Consequently, the city at that time had quite an important political significance.

According to Chinese chronicles of the 7th century, there were two capitals in the valley: the northern one - Kasan - was the residence of the Turkic rulers, in the southern one - Khumen - there was a representative of the local ruling dynasty. It has not yet been possible to localize the southern capital of Fergana. However, if we take into account the role of Kuva at the beginning of the USH century. it can be assumed that Humen of Chinese sources and Kubo of Arab authors are one and the same city.

The first large-scale archaeological excavations at the site were conducted by the Institute of History and Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan from 1956 to 1970 under the general supervision of Academician Yahya Gulyamov. The scientists worked in various parts of the city. Excavations have confirmed information from written sources that by the 10th century the main political unit of the city - the Ark (citadel of the city) had lost its importance and its walls were destroyed. The city itself, contrary to the opinion of some scientists about its gradual extinction, continued to remain a major political and cultural center in the Middle Ages until the beginning of the 19th century, when it was completely destroyed, apparently by the Mongol conquerors. The suburb of Kuva, north of Shakhristan, was excavated especially intensively in those years. Here, during 1958-1959, a Buddhist temple and a sanctuary were opened. The interior layout of the premises was well traced and the plan was completely restored. This complex functioned in the 7th century and was destroyed at the beginning of the 8th. The symbolism and stylistic features of the sculptural finds in Kuva leave no doubt that Ferghana was drawn into the sphere of influence of Buddhism before the Arab conquest. Other findings suggest that Buddhism was not the only religious teaching of the Kuvinians. During the excavations of 1956-1958, a fragment of an ossuary was found in a pit at the citadel, and in an excavation in the southeastern corner of Shahristan, the burial of bones in a ceramic vessel was discovered. These finds related to Zoroastrianism, as well as Buddhist temples, date back to the VI-VIII centuries. and they indicate that representatives of at least two religious communities lived in Kuva at the same time. To this can be added a Christian cross found during excavations in 1997 on the southeastern corner of Shahristan ancient Kuva.Due to a number of circumstances surrounding this find, it can be dated no later than the tenth century.

The first large-scale archaeological excavations at the site were conducted by the Institute of History and Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan from 1956 to 1970 under the general supervision of Academician Yahya Gulyamov. The scientists worked in various parts of the city. Excavations have confirmed information from written sources that by the 10th century the main political unit of the city - the Ark (citadel of the city) had lost its importance and its walls were destroyed. The city itself, contrary to the opinion of some scientists about its gradual extinction, continued to remain a major political and cultural center in the Middle Ages until the beginning of the 19th century, when it was completely destroyed, apparently by the Mongol conquerors. The suburb of Kuva, north of Shakhristan, was excavated especially intensively in those years. Here, during 1958-1959, a Buddhist temple and a sanctuary were opened. The interior layout of the premises was well traced and the plan was completely restored. This complex functioned in the 7th century and was destroyed at the beginning of the 8th. The symbolism and stylistic features of the sculptural finds in Kuva leave no doubt that Ferghana was drawn into the sphere of influence of Buddhism before the Arab conquest. Other findings suggest that Buddhism was not the only religious teaching of the Kuvinians. During the excavations of 1956-1958, a fragment of an ossuary was found in a pit at the citadel, and in an excavation in the southeastern corner of Shahristan, the burial of bones in a ceramic vessel was discovered. These finds related to Zoroastrianism, as well as Buddhist temples, date back to the VI-VIII centuries. and they indicate that representatives of at least two religious communities lived in Kuva at the same time. To this can be added a Christian cross found during excavations in 1997 on the southeastern corner of Shahristan ancient Kuva.Due to a number of circumstances surrounding this find, it can be dated no later than the tenth century.

Excavations in recent years (from 1996 to 2006) at the south-eastern corner of the remaining intact part of the Kuva site have revealed significant sections of the city walls that protected the ancient city from the east and south, and the angle between these walls. The preserved height of the walls in this place exceeds 4 m.

Excavations in recent years (from 1996 to 2006) at the south-eastern corner of the remaining intact part of the Kuva site have revealed significant sections of the city walls that protected the ancient city from the east and south, and the angle between these walls. The preserved height of the walls in this place exceeds 4 m.

The remains of the gate to enter the city through the southern wall, opened in the south-eastern corner of Shahristan, are of particular interest to archaeologists and architectural historians. Before this discovery, it was believed that there were only two gates on the entire perimeter of the walls of medieval Kuva. The excavations of the stone structures adjacent to the southern city wall and the architectural details of the design of the gate itself make it possible to study the layout and fortification features of the entrance to the medieval city of Central Asia, not in separate pieces, as it was on the objects radiated earlier, but having an almost complete layout for the level of the CP. Careful cleaning of the details of the gate structure showed that the passage existed at an earlier time.

During the work in the southern part of the ancient city of Kuva, the object of the study was the southern defensive wall. However, none of the excavations have revealed the remains of defensive structures that could be dated to a time earlier than the present century. our era.

The area of the city was not the same at all times. Significant surface depressions are visible along the southern and western walls of the city. Under the elevations, clearly visible on the surface of the archaeological site, a section of the city wall of the first centuries AD was discovered. e., therefore, the area of Kuva at the beginning of our era was half as large as in the early Middle Ages.

Interesting information was obtained about the oldest layers of the city. In the 50s, it turned out that the area of 12 hectares occupied by the Ark and Shahristan of ancient Kuva, by the VI century. it no longer satisfied the residents of the city, and the buildings spilled out beyond the northern defensive wall. In addition, the section of the northern wall showed that there were remnants of some defensive structures of the beginning of our era under it. In general, the results of the work of the 50s and 60s; a large number of ceramics from the first centuries of our era found in various parts of Shahristan, the remains of defensive structures of the same time and the finds of two bronze arrowheads dating back to no later than the 1st century BC — allowed us to believe that the city of Kuva originated at the turn of the century.

The idea of the date of the early layers of the city has changed due to excavations in recent years.

In 1996, a bronze arrowhead was found at an excavation site in the southeastern corner of Shahristan. Exactly the same tips with a hidden sleeve for the nozzle on the arrow and three downward-pointing stingers (ribs) were previously found on the territory of the Ferghana Valley in the burial grounds of the Early Iron period. They date back, by analogy with those found in the Pamirs, to the 5th century BC. A more massive early material was obtained during excavations in 1998. Layers with complexes of ancient ceramics of a very characteristic appearance were discovered at two sites at once — in the excavation at the southeastern corner of Shahristan and under the southern defensive wall. Most of the shards found in these layers were from hand-sculpted vessels, their surface is covered with light or red angob. Some of the shards still have traces of painting with red paint. According to the technological features and the shape of the vessels, this complex of ceramics belongs to the monuments of the Eilatan culture, widespread in the central part of the Ferghana Valley in the VI - III centuries BC. The Kuva finds, according to a number of signs, belong to the late period of this culture, but at the same time, the lower layers of the Kuva Shahristan should date back about 2.5 thousand years to the present day.

Many years of excavations in Couva, in addition to valuable historical information, yielded many thousands of objects of museum value. Moreover, there is no doubt that these products were manufactured in Couva, since archaeologists have discovered workshops of blacksmiths, glassmakers, ceramicists, tanners, etc.

Medieval glassblowers achieved special perfection. Many objects of various purposes were made of colored glass, from jewelry to pots in children's cradles. A large number of finds of glass objects in Kuva were noticed during the excavations of the fifties. The works of recent years have also produced a significant number of glass products. Most of all, glass glasses and glasses of various shapes were found. They were made by blowing into a mold. Glass vessels were distinguished not only by the elegance of their shapes, they were often covered with stucco or cut patterns that gave the products a certain personality. Kuva craftsmen were very fond of the technique of applying patterns using thin glued glass threads. Often these threads were made of glass of a different color than the vessel itself. This gave a special flavor to the product.

During excavations in 1996, a room with a special oven was discovered on the south-eastern corner of the city, where in the 12th century. produced glass products. Among the numerous fragments found on the floor were some that showed that glass for windows in the form of small flat glass disks was produced in Couva at that time.

The Ferghana Valley is rich in minerals. The iron and copper mines of the surrounding mountains began to be developed in ancient times. The production of metal products themselves was concentrated in large cities. It has long been known that one of these craft centers was the city of Kuva, on the territory of which fragments of crucibles — vessels for primitive steel cooking were repeatedly found. During the excavations in 1998, a vivid confirmation of this was discovered. One of the rooms opened in the area of the southeastern gate of the city was literally filled with waste from metallurgical production. There was a thick layer of ash and ashes above the floor of this room, in which a lot of pieces of iron slag and porous, frozen clumps of foreign impurities thrown out during metal smelting were found. In the middle of the room were the remains of a fairly large furnace with badly burned walls and a thick layer of ash inside. Not far from it, two oval pits were cleared, dug into the floor to accommodate the craftsmen in front of the forge. Exactly the same pits can be observed in modern artisanal forges, which are still preserved in a number of cities of Uzbekistan. The finds of numerous iron objects, including nails, horseshoes, fragments of knives and even a piece of defensive armor in the form of breastplates, indicate that the open room of the XII century was an ironworking workshop (forge).

Special rooms where bronze products were made have not yet been found in Kuva. At the same time, a large number of household and jewelry items made of non-ferrous metals were found in various parts of the settlement, where archaeological excavations were carried out, among which there are especially many items made of copper and its alloys. Archaeologists found parts of metal utensils in the Kuva, as well as an entire bronze bowl, a lamp leg cast in bronze in the shape of a mythical animal's leg, bronze hinges and fasteners from leather chests, various buckles from waist belts, bronze mirrors, bracelets, bells, earrings and much more. Special vessels were made of bronze for the preparation of eyebrow paint — antimony. All this was done at a high artistic level, despite the obvious serial nature of many of the items found in Kuva. The finds of a large number of similar objects made of copper and its alloys in the settlement, the assumption that the city produced its own copper coins, which were mentioned above, and the finds of characteristic slag remaining in the copper casting process, give reason to say that the city had its own production of copper and bronze products.

Special rooms where bronze products were made have not yet been found in Kuva. At the same time, a large number of household and jewelry items made of non-ferrous metals were found in various parts of the settlement, where archaeological excavations were carried out, among which there are especially many items made of copper and its alloys. Archaeologists found parts of metal utensils in the Kuva, as well as an entire bronze bowl, a lamp leg cast in bronze in the shape of a mythical animal's leg, bronze hinges and fasteners from leather chests, various buckles from waist belts, bronze mirrors, bracelets, bells, earrings and much more. Special vessels were made of bronze for the preparation of eyebrow paint — antimony. All this was done at a high artistic level, despite the obvious serial nature of many of the items found in Kuva. The finds of a large number of similar objects made of copper and its alloys in the settlement, the assumption that the city produced its own copper coins, which were mentioned above, and the finds of characteristic slag remaining in the copper casting process, give reason to say that the city had its own production of copper and bronze products.

The workshop where the leather was made was opened in an excavation in the southeastern corner of the city. During the excavation of one of the premises, which is part of the complex of buildings of a fairly large household, several finds were made indicating its functional purpose. The floor of this room was well rammed. Three rectangular buildings made of burnt bricks lying flat on one row are open on it. The walls of the buildings and the interior are coated with a layer of alabaster up to three centimeters thick. It is known that in ancient times layers of alabaster were often used for waterproofing. Therefore, the purpose of the found buildings was determined as baths. A stone veneer for leather dressing was found in the filling above the floor of the room. According to the totality of the finds, it can be assumed that in this room there was a workshop for processing animal skins in order to obtain leather for handicrafts.

Numerous finds of processed but unfinished crafts made of semi-precious stones in one of the rooms of a preserved complex of residential buildings of the 12th century. in the territory of excavation No. 4 suggest that an ancient jeweler worked in this place. Similar rooms, on the floor of which unfinished stone artifacts were found, processed for jewelry purposes, were found on the territory of the Kuva settlement before. One such room, identified as a jewelry workshop, was excavated in the late 50s among a complex of residential buildings near Buddhist temples .

The most massive material of all that was obtained during the long-term excavations at the Kuva settlement, of course, were fragments and whole ceramic products. Despite the fact that no premises have been opened so far that could be confidently considered a pottery workshop, indirect data allow us to safely assert that most of these ceramic products were produced in Kuva itself - this is proved by chemical analyses of some of the shards found at the settlement. The main part of the clay from which they were made is of local origin and is identical to the clay mined in the Kuva district and used by modern craftsmen in the production of ovens for baking bread. It is quite natural that over the more than two thousand years of the city's development, the style and shapes of ceramic products produced in Kuva have undergone significant changes. The tableware of the middle of the first millennium BC stands out sharply from the general complex — first of all, by the fact that most of it is made without the use of a potter's wheel. Stucco ware was usually covered with angob of reddish or cream shades. Easel ware, the number of which gradually increased from century to century, was usually covered with white angob. Sometimes, a geometric or floral pattern was applied to the surface of the angobed products with red paint. The number of such a characteristic shape for tableware as jugs begins to gradually increase only from the second century BC. At this time, the style of pottery is changing. The main part of the dishes was made on a potter's wheel. Ceramics were mainly made of thin-walled, very high quality. Most of the products of the new period, which lasted from the II century BC up to the VI century AD, were covered with high-quality red or black angob. Around the middle of this period, a geometric or floral ornament was drawn along the angob.

The political influence of the nomadic Turkic peoples in Central Asia affected the ceramics of Kuva (as well as the ceramics of the Ferghana Valley as a whole) of the 6th - 8th centuries. This influence is manifested in a gradual increase in the number of dishes of the Turkic-Sogdian type. Starting from the 6th century, high-quality engobe on Fergana vessels gradually disappeared; forms such as stemmed glasses and mugs with a loop-shaped handle became popular. The shape of many vessels from Kuva of the Turkic period copies metal and wooden samples.

By the 9th century, the technology of manufacturing glazed glazed ceramics was widely spread throughout Central Asia. The Ferghana Valley was not spared this process either. Glazed ceramics very quickly becomes the main one among Kuva tableware. In the X-XII centuries, Cuban craftsmen widely used polychrome underglaze painting of vessels. Geometric or floral patterns were usually applied, but sometimes there are also plot compositions. Many of the vessels of that time, made in Kuva, were made at a very high professional level. In terms of their quality and artistic level, they are not only not inferior, but often surpass the best examples of ceramics from recognized medieval ceramic centers of Central Asia.

Cuban medieval craftsmen who made unglazed dishes achieved no less skill. From the multitude of their products, vessels on three legs stand out - tripods. Such vessels, made of gray clay, have always been richly ornamented with several composite belts. The ornament was applied by cutting triangles and rhombuses in still soft clay and imprints of various stamps.

The city has always been a center for the manufacture of handicrafts for its district. The larger the city was, the more important it was in the economy of the region. Therefore, the study of craft workshops and the products of artisans of ancient and medieval Alas is of great importance for a proper understanding of the economy of ancient Ferghana as a whole.

Despite the fact that significant results have been obtained during many years of excavations at the Kuva settlement, archaeologists still face many unresolved questions, among which the most important are the question of the time of the first settlements on the territory of the city and the question of its political status in different eras.